This post is also available in: Español (Spanish) English

Llegiu l’article que va publicar Crític sobre el Grup d’Activitat Cooperativitzada Transitant, a femProcomuns, que vol contribuir a treballar i gestionar de manera col·lectiva l’economia, la cultura i la societat.

Ignasi Franch. Crític

La cooperativa Societat Minera Olesana, la comunitat energètica Solbrai o el grup que habita Can Tonal, de Vallbona, són iniciatives diverses que organitzen la seva governança de forma col·lectiva.

El capitalisme de l’escassetat i de les crisis continua recomanant-nos que trobem solucions individuals a problemes estructurals. Però la magnitud de reptes com el de l’escalfament global recomana que repensem la nostra manera de viure i que ho fem col·lectivament. La cooperativa integral de treball i consum femProcomuns ha posat el seu gra de sorra en aquest sentit amb la feina que fan des del Grup d’Activitat Cooperativitzada Transitant, que vol contribuir a treballar i gestionar de manera col·lectiva l’economia, la cultura i la societat. La iniciativa ha començat a implementar-ho en àmbits essencials com l’energia, la gestió de l’aigua o el problema persistent de l’habitatge.

El primer pas per entendre com es treballa de forma col·lectiva és saber que, perquè hi hagi un procomú, cal que una comunitat custodiï un recurs i es doti d’unes regles per fer-ho. Aquest recurs no estarà sota control i ús exclusiu de cap persona concreta. Alguns d’aquests recursos són obvis, com l’aigua, encara que la mercantilització del món hagi suposat privatitzacions de tota mena de recursos naturals. Per a David Gómez, membre de femProcomuns, la terminologia no és el més important: “Hi ha solucions comunitàries que són un procomú, però que no necessàriament s’anomenen o s’identifiquen així. És la gent de l’acadèmia qui posa el nom a la cosa”. Segons Mònica Garriga, també sòcia de femProcomuns, “hi ha moltes definicions de què són els procomuns, però sobretot són maneres de fer. El procomú comença a la cuina de cada casa i no s’ha de vincular necessàriament amb un model polític”.

Perquè hi hagi un procomú, cal que una comunitat custodiï un recurs i es doti d’unes regles per fer-ho

Per què apostar pels procomuns? Garriga considera que “cada vegada es fa més necessari no dependre del mercat capitalista perquè ja sabem on ens porta, a una situació tràgica de crisi climàtica, econòmica, social… Així que hem de buscar models on treballem conjuntament per autoorganitzar-nos. Hem de treballar amb l’Administració pública a través d’acords, pactes i convenis, però des de la nostra capacitat organitzativa”. Aquest fou el leitmotiv que va empènyer Transitant a treballar en iniciatives com La Comunificadora, un programa acollit per Barcelona Activa que va sevir d’incubadora d’iniciatives d’economia social. Amb aquella experiència a la motxilla, l’organització va impulsar el projecte Ecosistema Transitant, a través del qual ha convocat persones diferents i entitats diferents que poguessin compartir una certa sensibilitat al voltant d’un mateix tema per començar a treballar de manera comuna l’organització i la presa de decisions.

L’aigua, un bé escàs que es pot gestionar d’una altra manera

Quina gestió podem fer al voltant d’un bé essencial i escàs com l’aigua perquè sigui col·lectiva i democràtica? Una de les entitats que van participar en les sessions de Transitant va ser la Comunitat Minera Olesana, una societat amb més de 150 anys d’història que es va constituir com a cooperativa als anys noranta i que abasteix Olesa de Montserrat. Manté relacions amb proveïdors locals, alguns dels quals són cooperatives amb les quals mantenen una relació d’intercooperació i han format una cooperativa de segon grau (Aigua.coop). L’augment del cost de l’energia ha fet que la Comunitat Minera Olesana hagi instal·lat plaques fotovoltaiques.

La Comunitat Minera Olesana té més de 10.000 socis i ha creat un Consell del Consumidor com a enllaç amb el Consell Rector

L’entitat assumeix el repte de fer front a la pobresa energètica assegurant que no es talli l’aigua a ningú, amb un fons social, i d’estimular la participació: són més de 10.000 socis, però a les assemblees n’assisteixen uns 80 o 100. Per aquest motiu, han creat el Consell del Consumidor, un òrgan que fa d’enllaç entre l’Assemblea i el Consell Rector. Joan Arévalo i Vilà, president de la Societat, afirma que “va ser molt enriquidor posar en comú la gestió de l’aigua, treballar el seu potencial d’apoderament social compartit amb altres objectius de béns comuns i fomentar la intercooperació”.

Enfrontar-se a la crisi energètica comunitàriament

En el grup de treball sobre l’energia —com es produeix, es transporta, es transforma i es fa servir contribueix a modelar el tipus de societat i la seva relació amb l’entorn natural— va participar, entre altres actors, l’Ajuntament del Pinell de Brai, que impulsa la comunitat energètica cooperativa Solbrai juntament amb la cooperativa Azimut 360 i el grup ecologista GEPEC. L’objectiu és instal·lar plaques fotovoltaiques en diversos espais, des del poliesportiu municipal fins a propietats particulars, per aspirar a l’autosuficiència energètica i per escapar-se del model agressiu de grans instal·lacions de generació d’energia eòlica.

La comunitat energètica de Solbrai vol que el manteniment de les seves instal·lacions el facin professionals locals o la brigada municipal

L’alcaldessa del Pinell de Brai, Eva Amposta, afirma que espais de reflexió conjunts com el que ha impulsat Transitant permeten “qüestionar i millorar tot el que estàs fent. I sortir del marc mental que tenim interioritzats, on som consumidors d’energia i no ens plantegem cap altre aspecte”. Solbrai, la comunitat energètica que s’ha creat al Pinell de Brai, cerca la generació d’activitat a la seva localitat. Azimut 360 farà formacions perquè el manteniment de les instal·lacions sigui assumit per professionals locals, o, en cas que sigui necessari, per la brigada municipal. Es preveu mancomunar serveis amb altres cooperatives. Gómez, de femProcomuns, destaca la governança comunitària de l’entitat: l’Ajuntament només tindrà un vot a l’Assemblea. Amposta considera que els debats de Transitant els han refermat en la idea de plantejar “una iniciativa amb un tarannà total de participació ciutadana, que es desvincula dels models on una sola figura pot acabar controlant els projectes”.

Tenir un habitatge, molt més que un dret individual

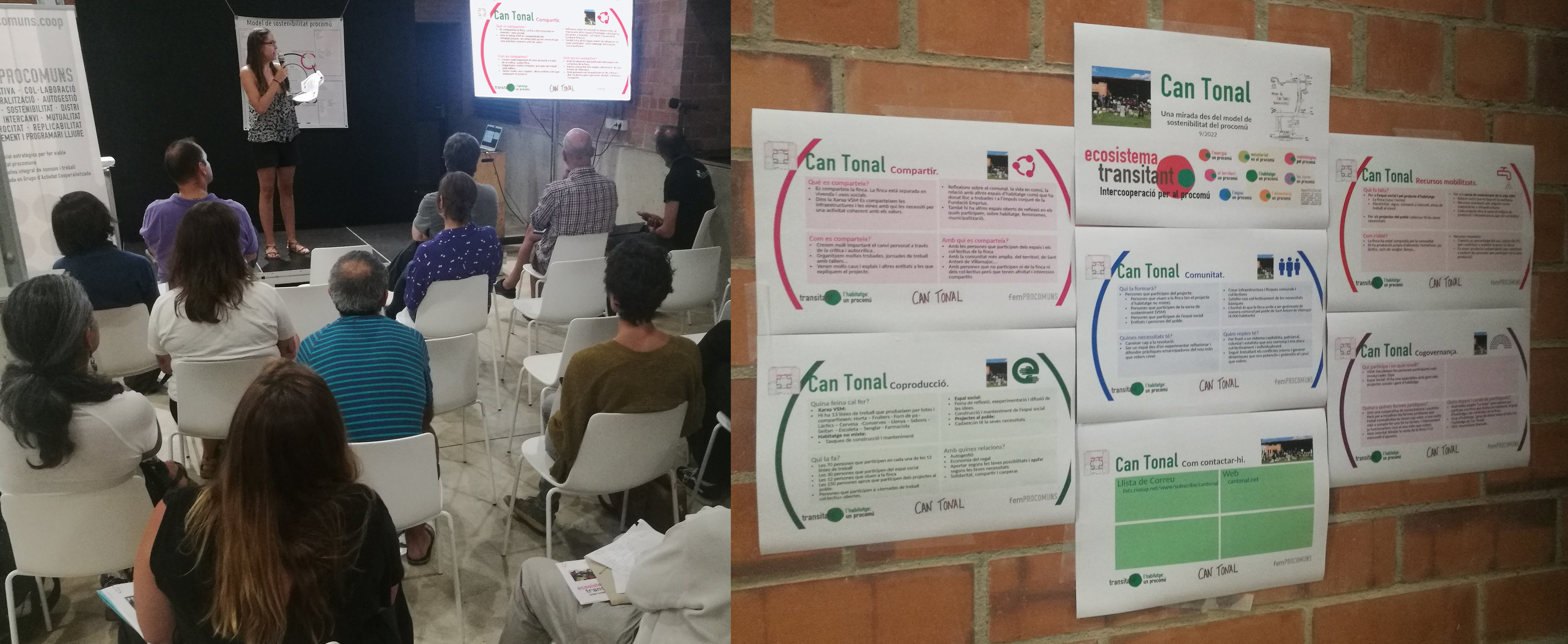

Dins de l’Ecosistema Transitant també van tenir lloc sessions de treball al voltant de l’habitatge, que, tot i ser bàsic per a unes condicions de vida dignes, no està recollit com a dret fonamental. Així, s’articulen iniciatives comunitàries autogestionades per dotar-se d’habitatge. Entre els participants hi havia membres de la comunitat de Can Tonal, de Vallbona, un projecte social que es desenvolupa en una finca del Baix Montseny que es trobava en estat d’abandonament. “Són unes 70 persones que comparteixen la feina, les infraestructures i les eines. Fan molt treball d’evolució personal. Fan jornades de treball col·lectiu obertes a qui vulgui, treballen molt de manera autogestionada, utilitzen l’economia del regal, i tenen aquesta idea que cadascú aporta segons les seves possibilitats i rep segons les seves necessitats”, explica Mònica Garriga, de femProcomuns.

A Can Tonal busquen sinergies amb altres projectes que treballen amb els procomuns per teixir complicitats

Des de Can Tonal destaquen que les sessions van permetre que compartissin experiències “amb altres projectes que treballen els procomuns i també conèixer persones molt interessants. Ens van ajudar a ampliar la perspectiva i adonar-nos que s’estan duent a terme moltes iniciatives arreu del territori. És possible que fem visites a algunes d’aquestes iniciatives, o que les rebem”. A Transitant van coincidir, per exemple, amb el supermercat per a persones vulnerables desenvolupat al voltant de la Plataforma d’Afectats per la Hipoteca i la Crisi de Sabadell, que agermana les respostes als problemes habitacionals amb els problemes d’accés a l’alimentació. A Can Tonal consideren que els procomuns poden servir de “vincle entre projectes aparentment de diferents àmbits”. I afirmen que és interessant “teixir una estratègia revolucionària que superi l’Estat, el patriarcat i el capitalisme, ja que és l’única manera realista de poder tenir una societat basada en els procomuns”.

Comunitat en temps de competitivitat

La idea de treballar maneres de fer més procomuns s’enfronta a un clima advers culturalment i ideològicament. La ciutadania és convidada a competir, en lloc de compartir. Gómez es mostra preocupat per aquest context, que també influeix en els projectes que tenen una certa vocació social i solidària. “Treballem la dimensió comunitària dels projectes perquè no veiem sentit al model de les empreses emergents, que està orientat que comencin moltes iniciatives, competeixin entre elles i només una arribi a consolidar-se. És tot un sistema que s’ha de desarticular, però resulta difícil entrar en la lògica de compartir”.

Garriga considera que el context social implicarà canvis en la manera d’organitzar-se: “Les situacions d’escassetat que estem experimentant poden facilitar que enfortim les maneres de funcionar que suposin que compartim recursos, com els cotxes, entre tots”. Gómez també dimensiona que els procomuns van més enllà dels factors econòmics, que no solament serveixen per gestionar un recurs d’una manera sostenible que permeti que continuï disponible per a generacions futures: “També signifiquen suport mutu, teixir lligams comunitaris”, recorda.

Pot ser important psicològicament sentir-se menys sol, però Garriga dimensiona un altre aspecte de la gestió comunitària dels recursos: que les societats on els coneixements flueixen són més horitzontals i més sobiranes. “Els procomuns també ens parlen de compartir coneixements perquè cap individu sigui clau, o perquè tots els individus ho siguem. Un coneixement distribuït permet una governança distribuïda i, per tant, prendre decisions informades“. Per a Gómez, tant el model de mercat com la gestió estatal “ofereixen serveis a través d’uns professionals emmarcats en una estructura jeràrquica, i això et deixa en una posició de passivitat. No has de conèixer res; només rebre el que se’t dona. Distribuir els sabers, en canvi, ens fa societats més resilients”.