This post is also available in: Català (Catalan) Español (Spanish)

Last May part of the femProcomuns team visited Quebec (Canada) to give some talks and workshops on the Commons Sustainability Model, to learn about Community and solidarity economy experiences and projects and also to participate in the The Great Transition. With this new blog entry, we’re complementing a previous text about this visit.

The Great Transition

For three days and for the third time,the headquarters of Concordia University, in the neighborhood of the same name in Montreal, hosted “The Great Transition“, organised by a collective of academics and activists who are part of the international network Historical materialism. The aim of this biannual meeting is to move from resistance to the transformation of society in order to get out of capitalism and to bring together critical knowledge that is produced, both in the academic sphere and in social movements, inviting people from different backgrounds and trends who share these goals.

With the subtitle “struggle in times of global crisis”, more than 900 participants and panelists from Quebec and all over the world met from 18 to 21 May to discuss the socio-ecological crises of the 21st century, whether they are the direct result of unbridled growth and capital accumulation, and what possible solutions might be, wheter the degrowth movement is enough, and wether other structural and systemic changes are needed. Struggles, initiatives, actions, tactics of resistance and transformation, socio-political organising, ecological stewardship, placemaking, conservation -some of which have worked better than others- were presented. And above all, strategies were discussed to strengthen existing struggles, create links and solidarity between them, and how to build alternative models of organising the economy.

Some of the issues that stand out from the programme are global justice, extractivism, decolonialism, ecological imperialism, eco-apartheit, intersectional class struggle, degrowth, ecosocialist revolution, radical rurality, the feminist struggle, the risks of gig economy, the emerging struggles in the global south, grassroots democracy, post-capitalism, Eurocentrism, anarchism, animism, people’s self-determination, digital resistance, … and also the socio-economic model of the commons.

Each afternoon there was a plenary session. The first on Post-capitalism outside Eurocentrism, with the Franco-Algerian activist Houria Bouteldja https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Houria.Bouteldja and the Honduran-born anthropologist Jairo I. Fúnez-Flores. https://twitter.com/Jairo.I.Funez, who researches on decolonization. The second was The reconfiguration of the Left in the World, with Mapuche linguist Elisa Loncón, Amazon trade unionist, Chris Smalls, and Palestinian physicist and activist, Mustafa Barghouti. The third connecting struggles for collective emancipation with the philosopher and activist Silvia Federici, Afro-American studies researcher and activist Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylorand Julian Lattimore of Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung. The closing plenary was on how to Repoliticize the climate question with the philosopher Mohamed Amer Meziane, Brazilian ecosocialist activist Sabrina Fernandesand geographer Matthew T. Huber.

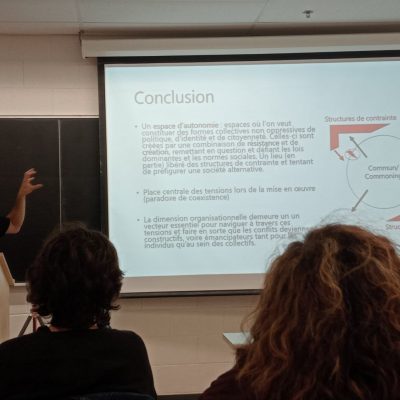

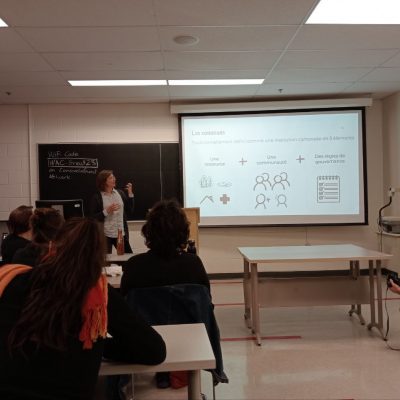

From femProcomuns we participated in the session “Transforming society for commons: international experiences and strategic perspectives”. Mònica Garriga explained the experience of the cooperative and the development and application of the Commons Sustainability Model. Jonathan Durand Folco, who facilitated the session, explained how municipalism can act as a springboard in the experience of Valparaíso(Chile), comparing it also to other cities as, such as Barcelona.Marie-Soleil L’Allierexplained her research on commons practices in Quebec; Marc D. Lachapellespoke of organisational practices to mediate tensions in commons projects; and Jonathan Veilletteon social empowerment policies in Puebla (Mexico).

We attended some sessions and met different organisations, initiatives, struggles and projects. Below we explain some of them.

Seize is a non-profit company -that operates according to the principles of cooperativism- which emerged from Concordia university itself, where the meeting was held, and which acts on three axes: organising, educating and incubating; as explained by Olivia Champagne, spokesperson for the project. Based on opportunities to take charge of the services linked to the university (such as canteens), it incubates projects to create cooperatives.

Giulia Falcone spoke about the experience of silk cultivation in Nova Esperança, in the state of Paraná, Brazil. She explained that this crop employs 2,500 families, but the industry is collapsing due to several factors such as climate change and, especially, pollution caused by pesticides sprayed from aeroplanes for neighbouring monocultures of soy, sugarcane, and other products. In 2006, the Maringà Technology Incubator, developed the project “Artesãos Brasil” that promotes the manufacture of handicraft products with silk thread. In 2010 Copraseda (Cooperativa dos Productores de Artesanato de Seda) was formally constituted with local farmers, producers of silk cocoons, who collaborate with “Artesãos Brasil”.

Quebec, like the rest of Canada and North America, is the result of European colonisation and struggles between different empires. It is also the result of prolonged policies of oppression and marginalisation of the indigenous population and their descendants; of dispossession and extractism. Philippe Blouin moderated a session about “Sovereingty and Indigenous Territories”. The Kanien’kehá:ka Kahnistensera (Mamas mohawk) discussed the dispute with MCGill University over the presence of unmarked graves of children, victims of medical experiments, on the site of the former Royal Victoria Hospital on Mount Royal Hill. For decades aboriginal children were separated from their families and re-educated in institutions where they lived in poor health conditions and were experimented on.

Waba Moko, Anishnaabe of the wolf clan in the Ottawa River Basin, spoke of the struggles of the Anishinaabe to protect the original wolf in their territory and to implement a hunting moratorium. Michaël Paul, protector of water and unceded sacred lands, an innu and nutshimiulnu. hereditary chief, spoke of opposition to the Treaty of Petapan, which threatens to extinguish the ancestral rights of the Nitassinan. And Yvan Boivin, an atikamekw activist from Mobilisation Matawinie Ekoni Aci, spoke of the blockade against logging in the Nitaskinan and how they have called for a 5-year moratorium so that nature to be reborn and biodiversity restored. In the meantime, they have built a barricade to prevent the entry of foresters and deforestation companies.

In one of the aforementioned plenary sessions Chris Smalls, president of the workers’ union of Amazon, explained the campaign for the creation of the company’s union. Smalls had been working there since 2013, and in 2020 he was asked to hide the fact that workers who had tested positive for COVID were still coming to work because they were not entitled to sick leave. This confirmed that the traditional syndicate was not working for them and they began the campaign—with two years of struggle—to create a new union. Smalls said that all struggles aganist capitalims must be united, and that in order to stop the exploitation of Amazon, he said, it is necessary not to buy from them, because if people continue to buy from them, one person in four will end up working for Amazon.

In the same session, Elisa Loncón from the Mapuche nation in Chile, warned about the loss of their own language, as a result of the minoritisation promoted by the school. She believes that both the left and the right, which emerged from the European continent, have used genocide to implement the philosophy of modernity, advocating that in order to achieve “progress” people must be sacrificed. She warned that improving human rights requires a new epistemology that takes into account indigenous cultures. The Constitution of 2021 (rejected in a referendum) marks a horizon for which to continue fighting: individual and also collective rights, parity and autonomy of the regions in a plurinational state.

With other participants in The Great Transition, we visited the Milton Park neighborhood and the self-managed space B.timent 7.

nbspnbsp;

Milton Park

Milton Park is one of Montreal’s old neighbourhoods, between downtown and the Mont Royal hill, after which the city is named. It is also an active communitywith an interesting history of struggle and building alternatives. Nathan McDonnell, a neighborhood activist, after taking part in The Great Transition, led a guided tour, where he explained the struggles, community projects and solidarity economy. It is a neighborhood with the traditional low houses of two or three floors maximum, that in the 1960s and 1970s was affected by a plan to redevelop it with the construction of mega-buildings. The neighborhood tenants confronted the project and organised themselves, without being able to prevent phase 1 and 2 of the urbanization from being carried out. Little by little, they bought up the houses that became empty, and so they cooperativised them. Today it is the largest non-profit cooperative housing area in North America, a type of community land trust.which includes housing and commercial premises, with 1,200 inhabitants.

Numerous environmental and community movements have sprung around Milton Park and also have contributed to the formation of the Self-organised Tenants Union of Montréal (SLAM-MATU) which is based on direct action to defend the tenants rights. Since the pandemic, other projects have been created around Milton Park, such as the cafe-bistro Bar Milton Park, a solidarity cooperative with a food bankand a community kitchenevery Friday (at noon and in the evening), food distribution for the most deprived, a co-working center and community library, among others.

Bâtiment 7

Bâtiment 7 is one of the most interesting projects of self-management of a space and strategies of strugglethat we have come across. It has many elements in common with self-managed spaces that we know in Catalonia, such as Can Sanpere in Premià de Mar, Can Fugarolas in Mataró or Can Batlló in La Bordeta neighborhood of Barcelona. It is located in Point-Saint-Charles, a post-industrial neighbourhood near the Saint-Laurent River, with a strong militant and community history. Its social and organisational fabric includes several housing cooperatives, community legal services, a popular education centre and the Clínique communautaire de santé. The area where Batiment 7 is located was a Canadian National Railway site, and the 8,000 square metre building, used to be a train repair and construction workshop. The real estate group of speculator Vincent Chiara bought all the land for 1 Canadian dollar (since the soil was contaminated) in a speculative operation to promote the Casino of Montréal, jointly financed by Loto Québec and the Cirque du Soleil. This was the begining of a neighbourhood struggle that has lasted 20 years. They denounced that the neighborhood needed space and that the company was taking a third of its surface area. They created theassociation “7 à nous“ (a play on words with “c’est à nous”, it is ours, it is up to us and this is our chance). After a long struggle with different stages, they managed to get the company to give the association the warehouse and 1 million dollars to rehabilitate it, as well as part of the development of the area for social housing, another for cooperative housing and a part for a park (the rest is market-rate housing).

It’s been five years since the space opened. They have renovated less than half of the space, but there is: a bar-restaurant (Les sans taverne worker cooperative) with its own beer production (12 different types!), it hosts concerts and cultural activities, a grocery store (le détour,(there are only a few grocery stores in the neighbourhood, a problem of many Montreal neighbourhoods is they have become “food deserts”, with nowhere to buy food and have to rely on cars), a bicycle workshop as well as carpentry, wrought iron, ceramics and laser cutting workshops, an art school, a library and revolutionary archive of struggles, a youth/teenage cooperative with a games and video games room, kitchen, sewing workshop and several multi-purpose spaces.

Outside there are vegetable gardens, a henhouse, and a structure made of containers that contains an approved kitchen where food is produced. In total there are 16 projects, some autonomous in the form of a cooperative or non-profit entity and others directly managed by the association. One characteristic of the project is its diversity. The book Bâtiment 7. Victorie populaire a Pointe-Saint-Charles» written by La Pointe libertaire, one of the collectives involved in the project, points out that one factor in the success of the struggle was the ability to bring together the ideological, strategic and tactical diversity of the different collectives and organisations involved, as well as the diversity of situations, origins and horizons of the people involved. This seems to remain a key factor in the current project.

Thanks

We want to thank Projet Collectif, and especially Marie-Soleil L’Allier and Jonathan Durand-Folco, for having invited us, for facilitating talks and workshops, as well as visits to projects and organizations. We also want to thank Samuel Raymond and Viviane Caron (and Spiky) for welcoming us into their home in Montreal. And we are very grateful to all the people who have shared their projects with us, who have dedicated their time to us and who have answered our questions and our curiosity to understand the different dimensions of the sustainability of what they are doing.

To Learn More

- Read the first entry we wrote about the visit to Quebec, what we went to do and other projects we knew about: Visit Quebec, the solidarity economy and community projects (I)

- La Grand Transition (see Program)

- Comité des Citoyen(ne)s Milton Park

- «Bâtiment 7. Victorie populaire a Pointe-Saint-Charles» (2013) La Pointe libertaire. Les Éditions Écosociété